Not long ago, the only way to tell whether a patient with dementia had Alzheimer’s disease was to do an autopsy for the presence of amyloid plaque and other signs of degeneration in the brain. In recent years, new tests can detect the presence of amyloid, a telltale protein of Alzheimer’s, and other biological signs long before the onset of symptoms. Soon, doctors may routinely make definitive diagnoses of Alzheimer’s with a simple blood test, even before symptoms of dementia become apparent.

An early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s is not worth much if there’s nothing you can do about it. But new effective treatments that slow the progress of the disease have become available: the drug lecanemab, recently approved by the FDA, and a new one called donanemab, which slowed cognitive decline in trials. The availability of effective treatments, together with technologies for detecting Alzheimer’s in the early stages, when those treatments can be most effective, have radically changed the outlook for Alzheimer’s patients and their loved ones. The notion of attacking Alzheimer’s in the brain before clinical symptoms emerge, long merely an aspiration, is starting to look like a practical strategy.

Advances in early detection and treatment come as welcome news, but they imply a looming public-health challenge. Being able to screen for Alzheimer’s and administer treatments before symptoms arise would vastly increase the number of people who need attention. Public-health institutions are almost universally inadequate for the task. There are large disparities in the impact of Alzheimer’s and in access to care in the U.S. and around the world. Pilot programs in communities around the world are showing how it might be done.

Meanwhile, the new optimism rippling through the research field is palpable. “Having been in this field for 20 years, the idea that I can finally offer treatments that biologically slow the disease is incredibly exciting,” says Gil Rabinovici, who directs the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of California, San Francisco. “There’s a lot more work to do, but the feeling is that our understanding and ability to measure and treat the disease is coming together in a new way.”

An enormous toll

About one in nine Americans over 65 have Alzheimer’s disease, according to figures from the Alzheimer’s Association. The numbers are higher for several segments of the population, including women, Black Americans and Hispanics. The number of people with Alzheimer’s is expected to more than double in 25 years.

It is a cruel, relentless disease. “It progressively robs you of who you are,” says neuroscientist Donna Wilcock, director of Indiana University’s Center for Neurodegenerative Disorders. Families carry much of the weight, she adds. The annual cost of Alzheimer’s care in the U.S. has reached $345 billion, the Alzheimer’s Association estimates—and that doesn’t count the $340 billion worth of unpaid care put in by an estimated 11 million family members and other caregivers of U.S. Alzheimer’s patients in 2022. Other estimates run even higher (see “The Ten Trillion Dollar Disease,” on page 24).

Modern medicine has made enormous strides in treating cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and even other neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis. But for years, everything medicine could throw at Alzheimer’s seemed to bounce off. The main research strategy has been to try to come up with drugs that attack the plaque that for more than a century has been known to be present in the brain tissue of deceased Alzheimer’s patients. But the dozens of experimental drugs that reduced brain plaque in mice with Alzheimer’s-like symptoms failed to make any detectable difference in cognitive decline in human drug trials.

Then, in 2021, a leap of progress came with the Food and Drug Administration approval of aducanumab, an amyloid-beta-attacking monoclonal antibody—a lab-made version of an antibody found in the human immune system. Aducanumab was the first drug ever approved for slowing cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s patients. But it was a controversial decision, in part because trial data showed at best hints of a possible small average slowing in cognitive decline.

Much of that uncertainty evaporated in January 2023, when the FDA approved a second plaque-fighting monoclonal antibody, lecanemab. This time, the regulators saw clear evidence that on average the drug slowed the cognitive decline in patients with early symptoms of Alzheimer’s. And that thrilling news was still reverberating through the research and patient communities when data released in July 2023 from a phase 3 trial of a third monoclonal antibody, donanemab showed additional promise, slowing the decline in memory and thinking by 35 percent compared to placebo. Almost half the study subjects who received donanemab showed no worsening of symptoms during a year of treatment, compared to only 29 percent in the placebo group.

“This is one of the things that patients and families say is important to them—to stay at the same level longer to keep doing what they enjoy doing,” says Mark Mintun, who heads neuroscience research and development at Eli Lilly, the pharmaceutical company that developed donanemab.

The sudden appearance of helpful treatments has been revitalizing for both the patient and research communities, says Indiana University’s Wilcock. “Patients and families had lost a lot of hope, and this restores it,” she says. “I truly believe it’s the beginning of the successful treatment of the disease.”

Continually better drugs are likely to follow in a steady stream over the coming years and decades, experts say. Alzheimer’s research may be similar to multiple sclerosis, another complex neurological disease. The first approved drugs in the 1990s were about 30 percent effective, and now several drugs are more than 80 percent effective.

AXS Biomedical Animation Studio

Diagnostics breakthroughs

Several factors have led to the sudden emergence of effective drugs. One is that the newer drugs are aiming at the right kind of amyloid plaque. There are many types, most emerging from variations of the amyloid beta peptide, but research has gradually pointed at particular forms, giving drug developers more specific and fruitful targets. A second factor is the improving ability to produce monoclonal antibodies that are more effective at hitting their targets.

But what may be the biggest single factor in the breakthrough treatment progress isn’t really about the treatments themselves. Rather, it’s better diagnosis.

A positron emission tomography, or PET, scan, involves injecting a radioactive tracer compound into a patient and then scanning for photons emitted. If the tracer binds mostly to something in the body associated with a particular disease, then the scan can be useful in diagnosis. PET scans capable of detecting amyloid beta plaque in living human patients have been around since 2004, but the early versions required massive machines that cost more than a million dollars to install, and even then the results didn’t give a reliable diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. It wasn’t until 2017 that affordable PET scans became capable of reliable plaque-based Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis.

When clinicians and researchers started accumulating results from those scans, they discovered two things. First, as many of 30 percent of people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease based on cognitive assessments didn’t have high levels of the plaque, which meant they had a different type of dementia and had been misdiagnosed. Thus, some of the plaque-reducing drugs that had failed in earlier trials probably hadn’t done as well as they might have because they included patients who had a different condition that had little to do with plaque.

Second, PET scan data clearly demonstrated that people with no clinical symptoms sometimes had high levels of plaque, and those people would usually go on to develop symptoms years later. In other words, people with high levels of plaque but no signs of cognitive impairment were simply earlier in the disease progression.

Researchers had long believed that the biological seeds of Alzheimer’s are planted long before—even decades before—cognitive impairment is clearly diagnosable, but they had no way of knowing which people were on that path. With PET scans closing that gap, drug trials could include patients positively diagnosed, through detection of plaque, while in the earlier stages of the disease, when a plaque-clearing drug might have a better chance of heading off damage. What’s more, ongoing PET scans can quickly reveal whether a trial drug is actually reducing brain plaque, making it easier to focus on drugs that had the best chance of working. Perhaps most important, these scans can reliably identify patients who have the disease in order to know which ones will likely benefit from approved treatments.

All told, the ability to diagnose the disease more surely and earlier, and to track its biological progression, has helped revolutionize the effort to develop and prescribe treatments.

“We don’t have to wait for someone to have symptoms to know if they have cancer,” says UCSF’s Rabinovici. “But 100 years after the initial Alzheimer’s case reports, we were still diagnosing by clinical symptoms confirmed at autopsy. These scans represent the modernization of Alzheimer’s care.”

Even better, blood tests are emerging that can pick up biomarkers correlated with the buildup of amyloid plaque in the brain, at much lower cost and higher convenience than a PET scan or a spinal tap, the other way of detecting signs of plaque. Blood tests could eventually become a routine screen for people who are in their 50s, when someone on track to experience cognitive decline from Alzheimer’s in their 70s would probably already have detectable levels of plaque.

Better, less expensive and more convenient diagnostic tests also mean people could more easily get a shot at one of the new plaque-clearing drugs when they may be able to do the most good. Research has shown that patients with mild cognitive decline do better when treated in early stage of the disease. In presymptomatic patients—that is, those who show no cognitive decline, but test positive for plaque—it’s still unproven whether treating them with anti-plaque drugs is effective in slowing or preventing the disease. “It’s an incredibly important question,” says Madhav Thambisetty, chief of the clinical and translational neuroscience section at the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and a neurologist at Johns Hopkins University.

Two ongoing phase 3 drug trials intend to answer the question. The AHEAD 3-45 trial is testing the impact of lecanemab on the onset of clinical symptoms in people who currently have plaque but no symptoms; the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 3 trial is doing the same with donanemab. Both trials are planned to run through 2027.

Genetic testing, too, will be part of the diagnostics picture for Alzheimer’s. Patients can already be tested for the APOE4 gene. About one out of four people have one copy of the gene, which more than doubles the chances of developing Alzheimer’s, and one in 40 or so people have two copies, leading to roughly a 10-fold increase in risk. Researchers have also found APOE4 variations that appear to confer a lower risk of the disease. Over time, other genetic predispositions or protections from the disease are likely to emerge, and some may also lead to new drug targets and therapies.

Some researchers also point out that the hunt for ever-earlier signs of impending cognitive decline from Alzheimer’s, while a boon to research and early treatment, requires consideration of privacy and medical ethics issues. Other concerns with genetic and other testing for very early Alzheimer’s include the risk that the results could impact eligibility for employment, life insurance and long-term care.

Attacking the disease

The drug treatments that attack plaque are going to become increasingly effective, insist most researchers. Now that two anti-plaque drugs have been proven to slow the progress of cognitive decline, researchers and pharmaceutical companies can focus on new, better ways of hitting plaque. That may include new anti-plaque monoclonal antibodies that do a better job. Or it may be pills that work about as well but, unlike most antibodies, don’t need to be ‘infused’ into patients—a biweekly or monthly process in which the drug is slowly dribbled into the body through an intravenous tube, usually in a clinic setting, or sometimes at home with the help of a trained caregiver.

Eli Lilly, for example, is developing a monoclonal antibody called remternetug that in early trials appears effective against plaque and may also be easily injectable under the skin like a flu shot.

Whether through existing anti-plaque drugs or new ones, researchers expect to see more patients get more benefits as research and clinical experience help find ways to match the right drug to the right patients, and to zero in on the optimal doses and timing.

If there is a cloud hanging over the prospects for anti-plaque treatments, it is amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, or ARIA. ARIA are essentially small bleeds and minor swelling in the brain, first noticed more than a decade ago in MRI scans of patients who were taking some of the first experimental anti-plaque monoclonal antibodies (and also in some patients who were taking placebo). ARIA have continued to show up in a significant portion of patients in trials for these drugs. In most cases there are no symptoms or only mild ones such as headaches that usually clear up within a few months, but there have sometimes been serious events such as seizures, strokelike symptoms and even death. For that reason, lecanemab carries an FDA “black box” warning, reserved for only drugs with the most serious concerns.

Few researchers suggest that worries over ARIA merit halting the use of anti-plaque drugs, given how welcome the progress in treatment has been to the Alzheimer’s community and how dire the consequences of leaving the disease untreated. In addition, clinical trials are conducted on elderly patients with many comorbidities that can obscure the cause of symptoms. Still, many are calling for more research. “We have to try to understand the underlying mechanisms of ARIA,” says Wilcock. “And we’re in desperate need of biomarkers that would help us identify the patients at highest risk.” Ultimately, she says, it should be possible to identify each individual’s chances of being helped by an anti-plaque drug, along with the risk of being harmed, so that doctors, patients and families can make informed decisions about whether taking the drug makes sense. And hopefully drugs to prevent or dampen ARIA will emerge, she adds.

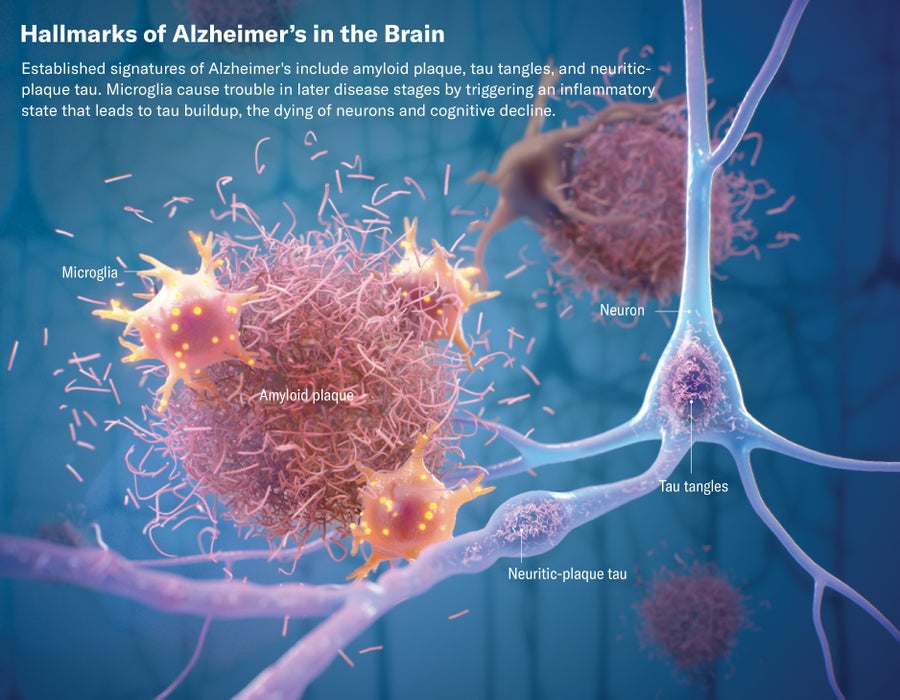

While anti-plaque strategies have been front and center when it comes to finding treatments for Alzheimer’s, another important approach has been gaining more attention recently. It involves going after the so-called tau tangles that spread through the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, particularly in the later stages.

Tau is a type of protein normally found within neurons, or brain cells, helping them to maintain their structure. But in Alzheimer’s disease these proteins detach, deform and stick together into tangled forms that ultimately damage the neuron. Although the exact mechanisms of Alzheimer’s remain cloudy, most researchers suspect that the buildup of plaque happens earlier in the disease, and the accumulating plaque eventually accelerates or even causes the formation and spread of tau tangles throughout the brain. Scientists used to think that amyloid and tau were competing theories but now believe they are part of the same disease cascade—that amyloid comes first and lays the groundwork for the formation of tau tangles, which is roughly when symptoms begin to emerge.

Evidence suggests that it is the tau tangles, more than the plaque, that directly cause cognitive decline. That theory received a boost from the trial for the experimental anti-plaque drug donanemab. The trial showed that the drug did more to slow cognitive decline among patients who had plaque but did not yet have high levels of tau tangles—patients saw progression of the disease slowed by up to 60 percent.

The implication of that finding is that reducing plaque can slow the accumulation of tau, but once tau has sufficiently accumulated reducing plaque alone may be not effective. “We’re already seeing a sequenced approach in drug trials, where first you try to clear out the plaque and then inject an anti-tau drug,” says Gauthier. “I suspect within two years we’ll see an effective anti-tau drug and within three years this will be the normal sequence of treatment for patients.”

Although plaque and tangles are the main targets of Alzheimer’s drug development efforts, other factors are known to play a role. Two of the biggest are brain inflammation and brain bleeding from damaged blood vessels. It isn’t known whether these factors become part of the disease, are risk factors for it, or are simply independent factors that exacerbate and accelerate cognitive decline.

Regardless of their relationship to the disease, researchers believe attacking these problems will give Alzheimer’s patients better outcomes. That means ultimately that patients will likely be treated with a combination of drugs.

“In 20 years, we’ll give patients different drugs for plaque and for tangles, and maybe each will slow the decline by 25 percent or more,” says Wilcock. “Then we’ll give them something for inflammation, and maybe that will slow it by another 20 percent. Then we’ll go after the health of their blood vessels and get another 15 percent. Little by little we’ll approach the point where we can bring the cognitive decline to a full stop.”

Disparities

Alzheimer’s puts a tremendous burden on patients, their caregivers and society at large. Patients lose years of productive life. Caregivers often sacrifice income to care for their loved ones who have the disease and their own mental health. All this has a huge impact on the world’s capacity to be productive—a trend that will only increase as populations age.

Medicine may soon be able to help by dramatically slowing or even halting the progression of Alzheimer’s. That raises concerns about how to get treatments to the people who most need them.

One concern is cost. In the U.S., most insurance plans will cover treatments, but deductibles, co-pays and caps will typically leave patients looking at many thousands of dollars in out-of-pocket costs. Only a fraction of the estimated 1 million patients in the U.S. who could qualify for treatments are likely to be able to afford them. In addition, some groups that are more likely to get Alzheimer’s disease, including Black Americans and Hispanics, also tend to have less access to adequate healthcare and to financial resources for covering out-of-pocket costs.

“This is an incredibly expensive disease,” says Rabinovici, “and we’re seeing disparities for minorities in every aspect of it, from inclusion in drug trials to access to specialty care. All of us involved in research and clinical care need to think about this and issue a collective call to action.”

The U.S. healthcare system is already struggling with a shortage of clinicians, both primary care and neurologists. That’s leaving many experts worrying how the system will cope with a growing number of Alzheimer’s patients, combined with a new diagnostic and treatment protocol that will demand more time and expertise on the part of clinicians. “We’re already scheduling patients six to 12 months out in our memory clinic, and we’re turning many away,” says Jeffrey Burns, a neurologist who co-directs the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of Kansas Medical Center. “That’s only going to get worse, especially as we develop ways to treat the disease earlier and earlier on and more patients push for those treatments.”

Burns’s center has pulled together tools that help train clinicians in how to help patients more effectively and efficiently and has recruited hundreds of primary care and other doctors and nurses into a support network to provide access to the tools and facilitate information sharing. Those types of supports will help, but Burns recognizes it will be a struggle to scale them up. “The challenges are magnified by the fragmented way our healthcare system is structured,” he says. “Different hospitals and practices use different medical-record systems and have their own care protocols.”

The U.S. public-health system, too, is fractured. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention can issue centralized guidance, but actual public-health policy and programs are developed and implemented at the state or even local level. That disconnect will pose another obstacle to managing Alzheimer’s, asserts Heather Snyder, a molecular biologist who serves as the vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association. That’s because coping with Alzheimer’s will require more than just better treatments for individual patients, Snyder explains. “It’s also going to take public-health actions that can impact behaviors at the population level,” she says.

That means raising awareness of the warning signs of the disease and the need to have a conversation with a physician about them, she says. It also means finding ways to get more people to adopt healthy lifestyles and follow doctors’ advice in order to limit heart disease, obesity, diabetes, and other chronic diseases to help prevent Alzheimer’s. To help, in 2023 the Alzheimer’s Association organized a summit in Atlanta of public-health experts and officials. “We need to engage state officials in thinking about how to bring the right risk-reduction messaging to the population,” says Snyder. “There’s a lot of work to do.” To compound the challenge, preventive medicine has long been a weak point in U.S. healthcare.

Issues of access are even more acute in poor nations whose healthcare systems struggle with less challenging diseases. “The kinds of healthcare resources we have in higher-income countries like the U.S. aren’t available in many countries around the world, including brain imaging and neurologists,” says Rabinovici. Not all healthcare systems around the world will make new anti-plaque and other Alzheimer’s drugs available, or cover most of its costs, experts say.

Some pilot programs are addressing various ideas of getting healthcare to Alzheimer’s patients. In Scotland, a pilot program funded by the Davos Alzheimer’s Collaborative (DAC) is beginning to include blood tests and digital-cognitive tests into the regular checkups and national health systems. In Armenia, as part of another DAC-funded program, health workers who go out in vans to administer routine checkups will soon have blood tests and digital assessments.

In spite of these many concerns, the overall feeling in the field is that things are finally moving fast in the right direction. “This is an incredibly hopeful and exciting time,” says Wilcock. “For the 24 years I’ve been in the field we’ve been telling patients that treatments were five years away. Now we can finally say we’re here.”

This article is part of The New Age of Alzheimer’s, a special report on the advances fueling hope for ending this devastating disease.