The skinniest pasta yet made—let’s call it “nanotini”—has an average diameter of 372 nanometers and only two ingredients: flour and formic acid. The latter, a caustic agent typically secreted by agitated ants, is why researcher Adam Clancy sniffed the creation before he tried eating it.

It is generally inadvisable to consume things pickled with formic acid, because ingesting as little as a tablespoon can be fatal. But Clancy, a chemist at University College London, relied on his understanding of the acid’s odor threshold—the lowest concentration at which the human nose can detect a substance. Clancy trusted that if the finished product was scentless, then it was essentially acid-free. Satisfied, he sampled a wad of nanotini. “I know you’re not meant to self-experiment, but I’d made the world’s smallest pasta,” Clancy says. “I couldn’t resist.”

Clancy and his co-authors, who recently published their pasta recipe in Nanoscale Advances, aren’t trying to whip up a menu item; they are investigating starch nanofibers for their potential as next-generation bandages. Mats of these fibers have pores that let water pass through but are too small for bacteria, Clancy says.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

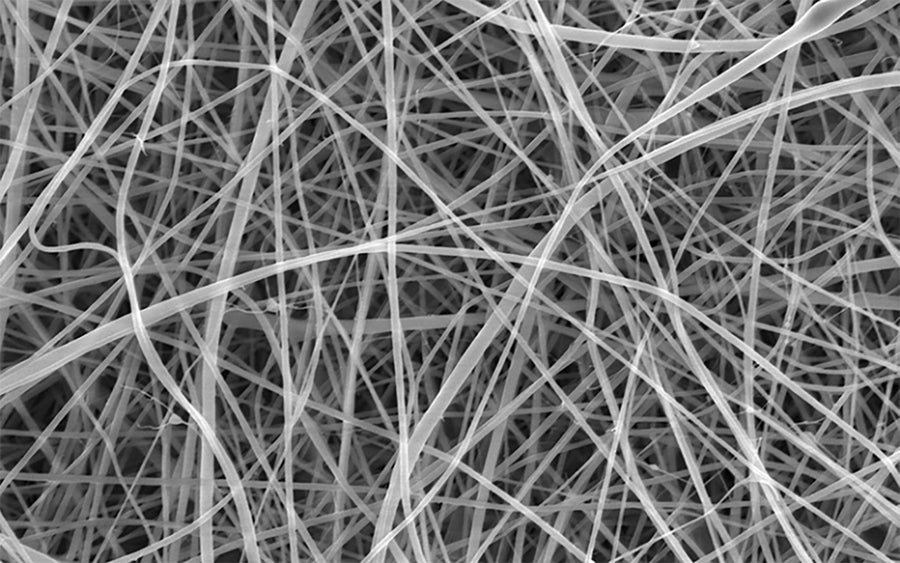

The team used a scanning electron microscope, scanning the mat with a focused beam of electrons and creating an image based on the pattern of electrons that are deflected or knocked-off. Each individual strand is too narrow to be clearly captured by any form of visible light camera or microscope.

Beatrice Britton/Adam Clancy

Ideal wound dressings aren’t simple barriers. They should also speed recovery, says Cornell University graduate student Mohsen Alishahi, who studies nanofiber bandages made with starch derivatives and wasn’t involved with the nanotini project. “Using a natural material such as starch to develop the wound dressing can help the wound heal more quickly,” Alishahi says. Starch should encourage cells around an injury to grow because the fibers resemble the body’s microscopic structural network, called the extracellular matrix. And starch has another natural advantage: it is made by every species of green plant and is one of the most common organic compounds on the planet.

Previous nanofibers had been built with purified starch from corn, potato and rice. This is the first time anyone has done so with plain white flour—thereby, Clancy claims, meeting the definition of the world’s smallest pasta. To make it, his team first dissolved the flour in acid, which uncoiled its starch clumps so the molecules could be stretched into skinny threads.

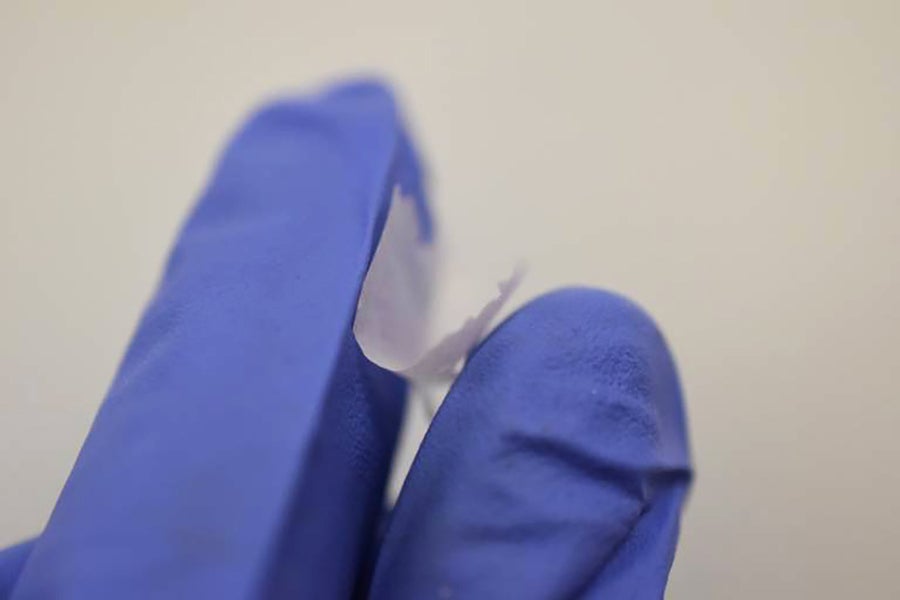

The nanofiber mat held between two fingers.

Beatrice Britton/Adam Clancy

The researchers employed a delicate sequence of heating and cooling to prepare the starch. This process is “the most interesting” aspect of the new research, says Pennsylvania State University food scientist Greg Ziegler, who studies starch nanofibers as possible scaffolds for cultured meat and wasn’t involved with the new paper. Despite the impurities of supermarket flour, the resulting liquid had the “proper viscosity for spinning,” Ziegler says, referring to the technique used to make the pasta.

Pasta makers typically slice dough or push it through small holes to give it shape. But in this case, the starch molecules were “electrospun”—pulled by electrical charge through a hollow needle tip. The liquid whipped out of the needle horizontally, attracted to a grounded plate a few centimeters away. As the acid swiftly dried in flight, the starch chains formed solid but invisible threads; their width was too small to be seen by the unaided eye. What could be seen were the off-white mats that formed when fibers amassed on the plate. These bendy mats looked a bit like tracing paper, but instead of wood pulp, it was exceptionally tiny pasta all the way down. As for the flavor? “I can confirm it needs some seasoning,” Clancy says.