A slab of seafloor that was around when Earth’s earliest known dinosaurs emerged has been discovered underneath the Pacific Ocean. It has seemingly hovered there in a kind of mid-dive for more than 120 million years.

In addition to illuminating geological processes deep inside Earth, the cold and dense descending rock, located some 410 to 660 kilometers below the planet’s surface, could explain a mysterious gap between two sections of a giant blob in the mantle layer.

A new study on the find, detailed in Science Advances, “provides a first present-day example of how a cold downwelling from above is breaking up a deep mantle blob,” says Sanne Cottaar, a global seismologist at the University of Cambridge, who wasn’t involved in the discovery.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Deep within our planet, two gargantuan, continent-size blobs of sizzling material rise from Earth’s hot, liquid outer core into its rock-filled mantle layer. Scientists can’t directly see these megastructures, which are hundreds of kilometers tall and thousands of kilometers wide. Instead researchers infer their existence from imaging techniques that rely on the way seismic waves travel through them. Within the blobs, seismic waves slow down, leading to these blobs’ more technical name, large low-shear-velocity provinces (LLSVPs). The larger and better understood LLSVP, colloquially called the African blob, sits under the East African Rift Valley, which runs from the Red Sea to Mozambique. There two tectonic plates are slowly moving apart and may eventually split the continent.

“At the East African rift zone, we have a present-day example of how a large hot upwelling mantle plume that originates at these deep mantle blobs starts to break up a continent,” Cottaar says.

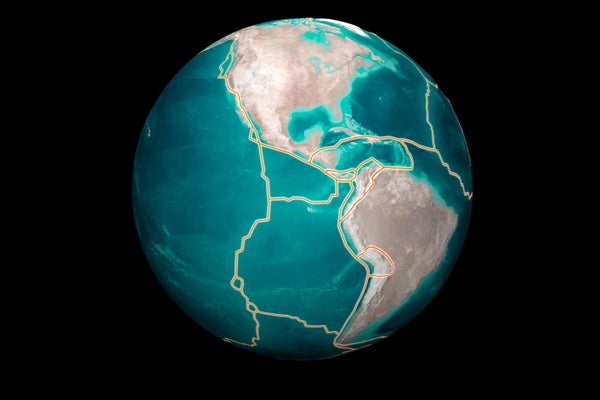

This illustrative diagram shows the ancient subducted "slab" the team imaged. This ancient seafloor slab has a direct impact on the large-scale structure called a mantle blob.

Jingchuan Wang, University of Maryland (CC BY-NC-SA)

Scientists aren’t sure exactly how these LLSVPs formed, what they are made of or how they contribute to surface events such as volcanism. Some research suggests they are relics of the collision that created our moon. “The general idea is that mantle blobs are most likely pushed around by subducted slabs,” Cottaar says, referring to the edges of oceanic plates that have descended below, or subducted, another plate. “The two main blobs are surrounded by ‘graveyards’ of subducted slabs.”

Jingchuan Wang, a geologist at the University of Maryland, College Park, and his colleagues were interested in examining the mantle blob under the Nazca Plate in the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of South America. Past research had suggested a structural anomaly exists there that seems to split the blob in half. In the new analysis, of earthquake waves traveling deep underground, the researchers saw evidence for something cold and dense stuck in that gap.

“The most parsimonious explanation for the cold temperature and high seismic velocity is the presence of a subducted slab,” Wang says. “But this area has no active subduction, and the imaged slab has already detached from the surface. Therefore, we believe we are observing an ancient slab.”

Wang’s team describes two possible scenarios for how this ancient seafloor ended up wedged in the middle of the Pacific mantle blob. In one, some 250 million years ago a broken-off edge of seafloor began to fall between the predecessor of the Nazca Plate and the part of the supercontinent Gondwana that later became South America. That broken plate part, which functioned as the seafloor during the early Mesozoic era, would have sunk below those two plates, whose boundary now forms the fastest-widening oceanic ridge in the world, called the East Pacific Rise. Alternatively, the descending slab might have dipped under the Nazca Plate’s predecessor, Wang says, in a bout of ancient tectonic reshuffling.

Regardless of how it got there, part of that seafloor is very slowly creeping downward at a pace of about 0.5 to one centimeter a year—nearly half the rate at which a similar object would sink if it were lodged just below this zone in the mantle. The thickness of the slab and the viscosity (or gumminess) of this region of the mantle, Wang says, could explain the slow sinking speed.

“Our findings help to link the plate tectonic history of the past 250 million years to present-day mantle structures,” Wang says, “providing clues about Earth’s complex past, in particular what was happening in the subsurface, which often leaves no discernible geological fingerprints on the surface.”